Robots That Work

Rodney Brooks, wheeled humanoids, and how to build for the future of Robotics

In late September Rodney Brooks published something that should be required reading for anyone investing in humanoid robots. Or building them. Or thinking about either.

I hope you won’t blame me for being some ~80 days late commenting on it. I’ll try to use this piece to spark a broader reflection.

Brooks isn’t some random skeptic. He co-founded iRobot (Roomba), built Baxter at Rethink Robotics, and spent decades running MIT’s CSAIL lab. His takes on robotics are usually worth paying attention to.

His essay, “Why Today’s Humanoids Won’t Learn Dexterity” makes three arguments that I want to unpack.

The first one introduces a question that I believe is worth expanding on. The second one is a great first-principles observations. The third one is something I have a strong opinion on.

Let me try to summarize them if you don’t have time to dive into Brooks’ original text:

One. Humanoids are definitionally human-like, which means they need human-like dexterity to perform valuable and fine tasks.

That’s the whole point: robots that can do what humans do, in spaces designed for humans, with tools designed for humans. The problem is that we are nowhere close to building generalizable dexterous robots. Brooks thinks this is because everyone’s trying to brute-force the input-to-action mapping without actually understanding the underlying physics of manipulation.

I’ll come back to this, but my hunch is that he may be right. In today’s robotics development landscape, the approach with the most talent density and venture investment seems to be that of Vision-Language-Action models (Chris Paxton here). VLAs do not model dexterity by understanding its physical intricacies, but try to make dexterity emerge from large dataset training and fine-tuned inference. It’s the same approach used by LLM/LVMs with the added difficulty that there is no touch/sensory-to-action equivalent of ImageNet out there to train these networks on ungodly amounts of data.

Two. Current humanoids are dangerous.

Not in a Terminator way, but rather in a “full-sized bipedal robot pumps enormous amounts of energy into staying upright, and when it falls, that energy goes somewhere” way. The scaling laws for this effect are brutal: a robot twice the size has eight times the kinetic energy in a fall. These machines will hurt people and will be a nightmare to certify.

This is just simple mechanics. Our tendons act like springs, we can walk around using very little power and it’s easy for us to amortize falls. Current humanoids are stiff, they counteract gravity by pushing hard into the ground when they get off balance (Zero-Moment Point). When they fall, all the energy transfers instantly. Energy-recycling tendons for humanoids are being researched, but what you see in production today is nowhere close.

If you want to get deeper and nerdy on humanoid actuators, you can watch this lecture or take a look at the last few slides of this presentation. The problem of non-passive mechanics for humanoids is so acute, that if you want a humanoid to just stand still for some time, the amount of constant current you need to jack through its actuators risks overheating it!

Three. Here’s where it gets interesting. Brooks predicts that soon, we’ll have plenty of “humanoid” robots around our factories and homes, but they won’t look like humans at all.

They’ll have wheels instead of legs. Multiple arms. Sensors in weird places, rather than familiar faces with eyes. The name might even stick even as the form factor evolves away from human morphology entirely. Essentially, we’ll optimize the form factor for fitness to a certain task, but we won’t care about human similarity.

I am aggressively in agreement with this last point. And I’d push it further.

The recent massive capital allocation into Western freakishly-human-like humanoids looks optimized for fund economics, rather than commercial viability.

Mega-funds need to deploy huge amounts of capital quickly and very few companies out there can claim on their pitch decks that, in the limit, their TAM equates “literally any physical task humans can do”. That’s the kind of pitch that justifies a multi-billion $ valuation before you’ve shipped a single production unit!

Meanwhile, something quieter is happening: wheeled robots and mobile manipulators are starting to generate actual revenue, all while their bipedal cousins still generate mostly headlines and TVPI.

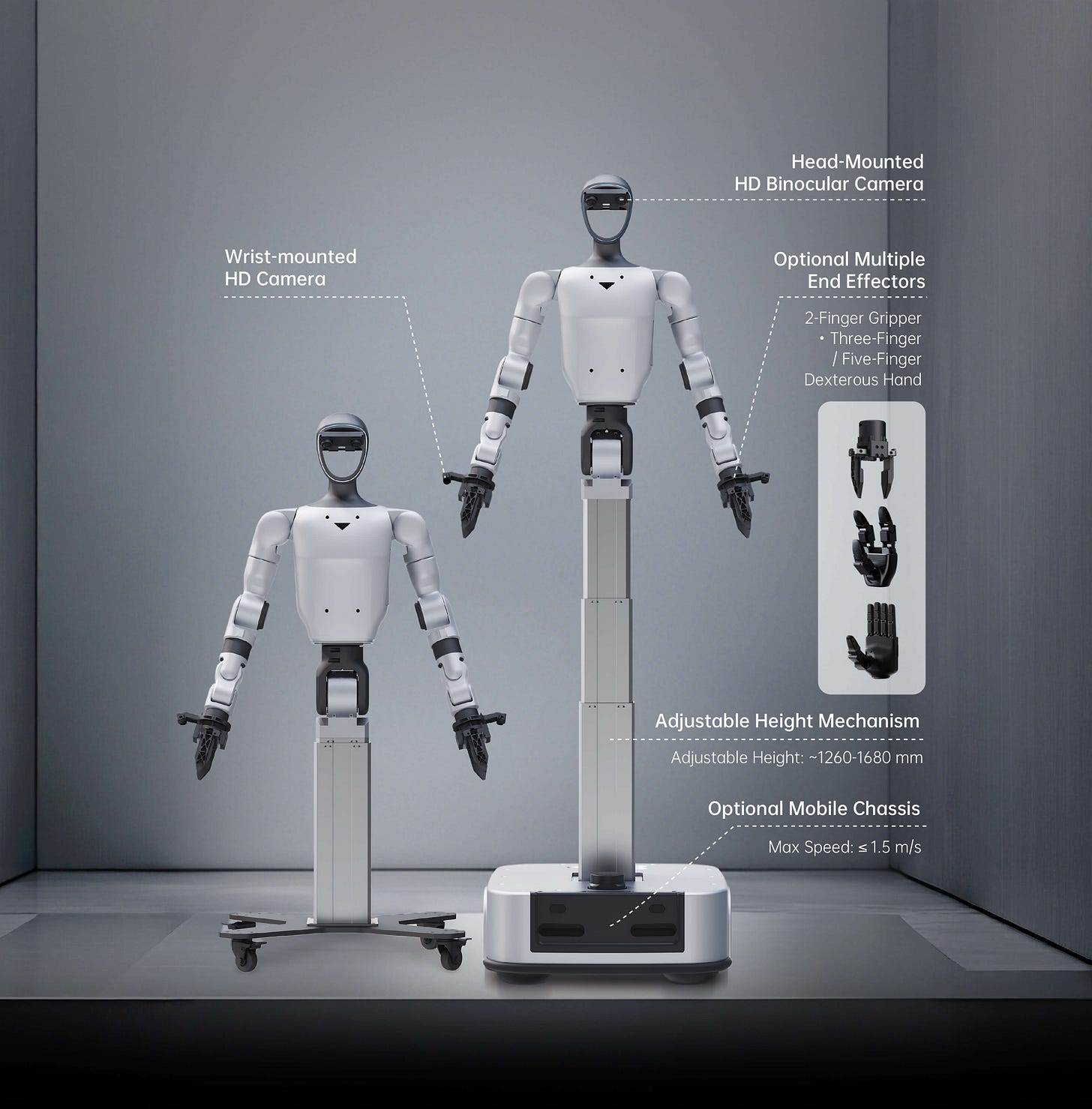

Unitree just announced (or rather re-announced, this time with a full software suite of data collection and world model natively integrated) the G1-D - a humanoid torso on wheels. They traded bipedal locomotion for 3x the battery life (6h - which is more than my Macbook running Matlab) and the stability needed for reliable operation.

It’s not as sexy, but it works.

Semi-humanoids are quick to deploy, battery-efficient, and bypass almost completely security concerns about the safety of legged machines.

Maybe the strategy here is: humanoids raise money, semi-humanoids and other uglier robots make money.

Nevertheless, as you may expect in a market this hungry for assets, semi-humanoids are raising money too: Sunday Robotics came out of stealth with a $35M investment led by Benchmark.

I think it’s worth knowing who the founders are:

Tony Zhao is one of the authors of ALOHA, a Stanford project that proved somewhat-dexterous manipulation can be done with cheap hardware and then open-sourced the whole thing. I know at least 4 founders that are building on the ALOHA platform.

Cheng Chi, main author of UMI, another open-source Stanford project focused on gathering data for manipulator robots in the wild without the robots having to be in the wild! Here’s what I mean.

I really like this duo of young roboticists because both of them worked with cheap, open-source hardware running software platforms focused on data collection and interoperability.

In the end, this is exactly what will be needed to compete with Asian robotics companies: Chinese humanoids are already cheap and mass produced, and despite “Western-companies-build-better-software” claims, Unitree’s open source software stack is a key driver for its global lead in sales of quadrupeds and humanoids to research lab market around the world.

E2E robotics isn’t deployment-ready yet

Whether you like humanoids or less-human form factors, you still have to solve dexterous manipulation if you want these machines to become ever-present equipment in our factories, warehouses, hospitals and homes.

This brings us to argument #1 of Brook’s essay.

I am nowhere near qualified to contribute significantly to the “end-to-end vs. fully deterministic robotics” debate from a deep technical perspective. The best I can do is to try to summarize it:

We are seeing some impressive research results and demos by teams that are applying end-to-end learning to make robots learn generalized policies. New models make it so that you can tell the robot “assemble this box” and with the right training processes (eg. lots of video and physical data, human tele-operated intervention to fix mistakes) it will do it.

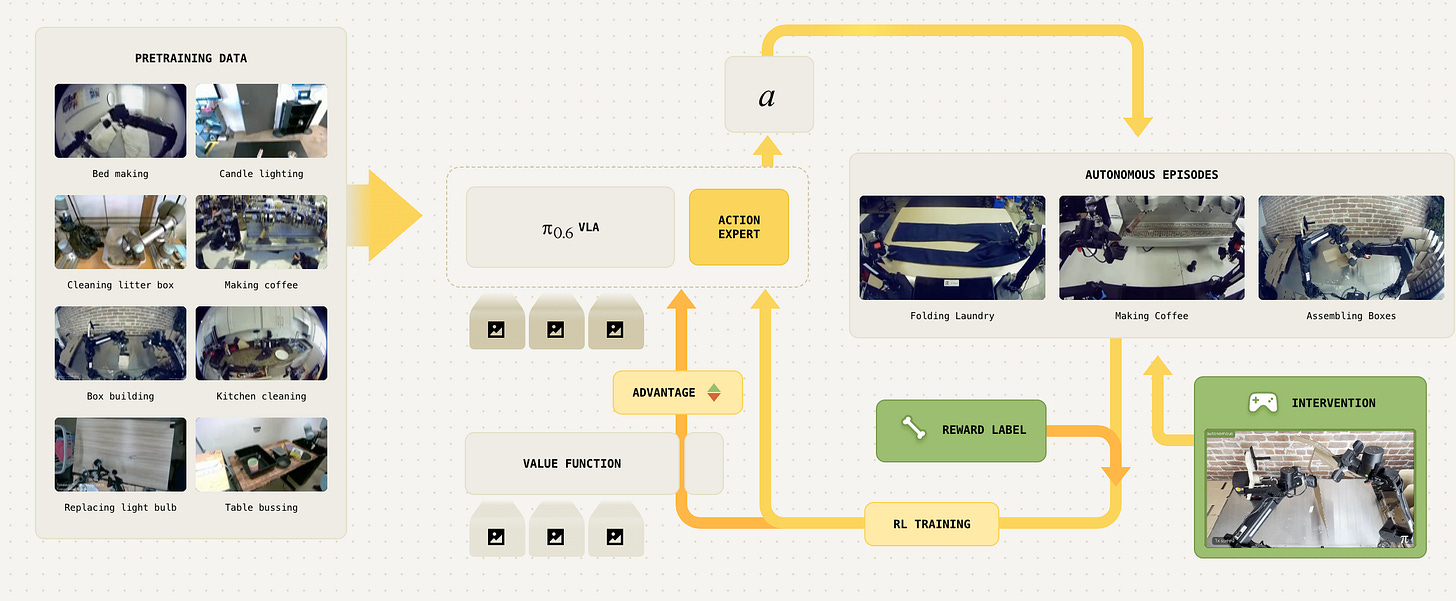

If you want to go deeper, the best resource is the π*0.6 announcement and paper. The Physical Intelligence team has done a great job to make their findings accessible.

However the task-specific throughput levels achieved by these systems, as well as their reliability and ease of deployment, are largely nowhere near what you would need for real-life deployments. You can’t afford to have significant downtime from a machine bought/leased to increase efficiency for your operations.

The bottleneck to build reliability is interpretability. This is quite obvious if we observe that VLAs rely on the transformer architecture that powers LLMs - which aren’t interpretable at all.

Both in development and production, it’s hard to troubleshoot why E2E systems are failing. If given an input, they spit out controls (joint positions and torque) based on their training. All we can do to improve them is test out more and more clever network and training architectures hoping that the next tests will yield lower failure rates.

We essentially don’t have a clear log of what’s happening inside the models, making it hard to architect the right step forward to improve them. It’s really easy to get stuck in local maxima.

The flip side of the coin is that the progress curve of these models is incredible. Physical Intelligence’s π*0.6 has shown what’s possible when you combine imitation and reinforcement learning: their RECAP framework trains robots with demonstrations, first, then corrections from human operators and then lets the robot practice on its own.

The number of tasks studied is very small and doesn’t quite give us evidence that we’re moving towards some sort of generalized intelligence. Yet, amazing progress is undeniable.

The open-source ecosystem is accelerating this. Hugging Face’s LeRobot has become something like the Transformers library for robotics—a unified framework integrating state-of-the-art models from Physical Intelligence, NVIDIA, and others. After acquiring Pollen Robotics, they’re even selling open-source hardware. The full stack is becoming accessible to developers. I actually just bought one.

And then there’s the data angle. Build AI just released 100,000 hours of first-person video footage from factory workers doing skilled tasks. Over 10 billion frames. The thesis is that egocentric human video could be for robotics what internet text was for LLMs: a massive, passively-collected training corpus that unlocks generalization.

More data doesn’t solve for interpretability, but it gives us a chance to land on progressively better local maxima.

How to build robots that work

Most enterprise robotics deployments are stuck on traditional approaches. There are good reasons for this. You can debug a state machine. You can’t debug a neural network that learned to fold laundry from watching humans.

But the ceiling on traditional approaches is visible. Every new task requires new engineering. Every edge case needs explicit handling. Nothing generalizes.

The answer isn’t choosing sides. It’s building infrastructure that lets you implement E2E progressively:

Deploy traditional systems that generate structured data as a byproduct. Every successful grasp, every navigation path, every intervention. Build your own vertical dataset from your form factor’s POV.

Implement E2E selectively, ideally into new test-features. Start where failure is recoverable and expand as reliability improves.

Maintain interpretable fallbacks: the ability to drop from learned behavior to traditional control when confidence is low. Very rarely will full automation be the core focus of your customers. In “Everyone wants to invest in robotics” I sketched out in more details how I think deployment-focused teams are building smart tools, rather than full automation.

A great way to control your destiny is to make your business model Outcome-as-a-Service: while you test out what works, you’re covering downtime with human labor. Margins start out lower, but the revenue and track record flywheel has started spinning.

The winners won’t be pure E2E or pure traditional.

They’ll be hybrid architectures where traditional systems provide the reliability floor and learned systems provide the capability ceiling.

I have no idea when I’ll be able to piece it together, but in the next article I’ll explore what happens when hardware differentiation converges to zero (think Chinese mass production, huge margin compression for the West etc.) what really counts is delivering outcomes and integrating seamlessly.

I remember 1x’s humanoid taking 5mins to close the dishwasher. In the meantime, you have enough time to visit all the countries in the world.